Adventures amidst the books

Given all the shapes and forms of connection available all the time today, using heavy books for research purposes might appear a little antiquated. However, libraries have kept an aura of knowledge, blended with respect in our collective imagination that the web has trouble providing us: it is as if we balance order with chaos, silence with noise, knowledge that endures through time with that used and consumed immediately.

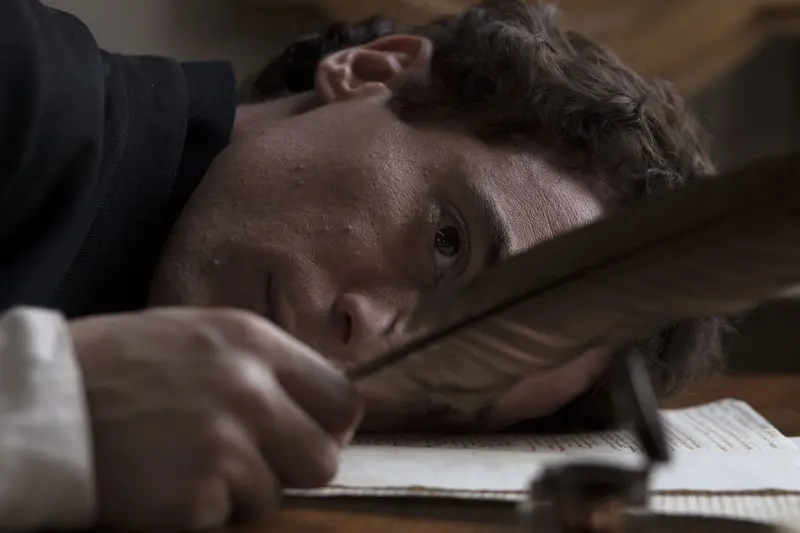

So when Robert Langdon (the fictional hero whose encyclopaedic knowledge we have come to know from Dan Brown’s books and the films where he is portrayed by actor Tom Hanks) searches the Vatican Libraries (a venue open to the privileged few) for the solution to a mystery in Angels and Demons (2009) and we watch powerlessly as the yellowed pages of ancient texts are shredded and entire rooms filled with books of inestimable value are destroyed, those who love these magical place are always relieved by the thought that “it’s just a film”. And while the Vatican Libraries are as inaccessible for location use as they are to us common mortals, the immense treasure conserved in Rome’s Biblioteca Angelica, setting for several scenes of the film, is intact and can be admired both on and off the screen.

When it comes to adventure, we can’t fail to mention the king of archaeologists, Indiana Jones (aka Harrison Ford), who, in one of his many exploits, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, travels to Venice to find clues about the Holy Grail. The mystery is revealed in the form of an inscription carved into a sarcophagus in the catacombs of a deconsecrated church, converted into a library. Called Biblioteca Marciana in the film, the external shots actually show the Church of Santa Barnaba. A panoramic shot shows us the library from above. However, it is impossible to see the places where the sequence was shot as they were built on a soundstage. The library, though, does exist, it is located in Piazzetta San Marco and houses, among other things, 620,000 printed books and 13,000 manuscripts: its monumental rooms are well worth a visit.